Dani

So you grew up in Chicago, and you've said before Chicago's urban planning was designed for segregation, which is something that I was thinking about a lot. In Chicago especially, it's a race-based segregation. How do you think that kind of urban planning impacts the creative output of the city?

Yashua

When there's segregation and a city is designed to separate people, it is an attempt to confine and define ways of moving and ways of accessing power and freedoms, which are all related to creativity and creative thinking. It was always interesting for me, because I grew up South Side Chicago in a neighborhood called Hyde Park, which was the one integrated community in the South Side. My mother's white, my father's black. Hyde Park was, in a way, a haven in the ’70s for interracial couples. Also, the World's Fair happened there and the University of Chicago also sprouted up in that area as a result of the World’s Fair. But there were a little more resources and access to the arts in that neighborhood. So, in a way, it was an oasis. Otherwise, South Side had been depleted of those creative resources.

I actually feel, to some degree — and I mentioned this in my artist statement about the grid — the grid is an obstacle that creates an opportunity for growth. In the same way that I would look at a wall meeting a sprawling vine. The vine thrives because it has the obstacle in front of it. It finds a way to grow, to break through the wall and find the cracks and the holes and the weak points in it, and it finds a way to gather the strength to overcome the wall, to overcome that obstacle —if it's lucky. To some degree, I relate that to Black resilience. Dealing with limitations, dealing with depleted resources, yet still finding a way. That resourcefulness.

"The grid is an obstacle that creates an opportunity for growth. In the same way that I would look at a wall meeting a sprawling vine. The vine thrives because it has the obstacle in front of it. It finds a way to grow, to break through the wall and find the cracks and the holes and the weak points in it, and it finds a way to gather the strength to overcome the wall, to overcome that obstacle — if it's lucky. To some degree, I relate that to Black resilience. Dealing with limitations, dealing with depleted resources, yet still finding a way. That resourcefulness."

In Chicago specifically, because of segregation, you have these small neighborhood institutions. One that was really pivotal for me was the South Side community art center, which is in the Bronzeville area of Chicago. It's in the hood, it’s totally low key. It was a former residence, so it looks like every other house on the block. It was funded in the ’40s WPA era, it was getting governmental funds to stay afloat. That’s what was happening in the ’40s. And some great artists came out of there: Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White — those are my heroes, you know?

When I was introduced to the South Side community art center, it was such a communal place — all of these artists from the South Side would meet there because there was nowhere else to go. It became our thing. It became our clubhouse, our meeting place. We had fish fries on Fridays, and it became a place to socialize and connect, because it was the one place that everybody knew about where the artists would be at. So, we made the best of not having much else. Knowing that we had community there was really empowering.

We were just talking about the gatekeeping that a big institution has, but because those walls are removed from an underfunded institution, you get access. You can see a Charles White in person there. I walked into the director's office one day and was just casually talking with him at his desk, and he was like “Oh, you like Charles White?” Without breaking eye contact with me, he reached under his desk, pulled out a framed Charles White woodblock print. That was a linocut that changed my life. When I saw that, I was like, I have to learn how to make linocuts. Because of that moment. And to know that Charles White was in this building, that was, to be honest, halfway broken down. They were having issues with the basement where the storage was, with keeping the artworks safe and dry, all those things that more well-funded institutions would obviously prioritize. They were having troubles with all of that, yet still, I had access to a Charles White print right there on the desk. You can't walk into most museums and get access to history like that.

That, to me, is an instance of finding ways to nurture growth through community, which is a necessary tool when segregation splits neighborhoods up and splits people up. What happens is, because you're divided and cut off from resources, you rely upon community as your resource. And I think you see that also coming out of a lot of artists’ work in Chicago today. Theaster Gates, for example, you can even say his medium is community. So there's that communal activity that you see coming out of places like South Side Chicago, which have been stricken by segregation and being cut off from resources. Your community becomes your resource.

Dani

That's powerful. I think that's absolutely true. It sounds like, within this community in Chicago, that you had not just someone, but many people to look up to. Even if Charles White wasn't there in person, his work was there and the feeling of his spirit was in the space — that's potent.

But you've also said that the toughest part of your career was when you were feeling kind of stuck with no role models. Since the art world is not black and white, there's no handbook that you can just read and know how to do it. Did that point of feeling stuck come later into your career, as you realized that you wanted to be an artist professionally? Did it come after you moved? How did you get past it?

Yashua

Again, I was saved by my relationship to community. I didn't know what to do next as an artist, because there is no handbook and there's nobody that's guiding you through it. And certainly in school, we weren't guided towards career decisions; we were guided in thinking and concept building and some craft. But my community saved me at that point, because I started to look at my peers as role models. There was a lot of peer to peer role modeling. I didn't have an OG or somebody that was an older mentor, so I looked at friends of mine who were either more experienced or, for whatever reason, just more informed. And actually, when I think about it, they were also more informed because they were very connected to community. I'm thinking of Derrick Adams, for example. He's always been a friend since I moved to New York. At that time, he was the director at Rush Arts, which was a nonprofit space that gave a lot of artists of color in New York their first show. So it was a hub, a meeting place for really all the young artists of color at that time, in the early 2000s, mid 2000s. He was so connected to community that I think he found a way to power up his career early on. I could lean on Derrick Adams; give him calls, ask him to come by the studio for studio visits.

I just started to really rely on my community, reach out to peers, and see what they were up to. Because once you're out of grad school, they don't tell you, but you actually have less. When you're in school, you have a studio, you have a community of people that are surrounding your work, talking and thinking about your work. When you graduate, you don't have the studio anymore, you don't have that network. So you have to build all that yourself. And that was the dry spell that I think a lot of artists go through — this kind of crash after grad school, where it's kind of anti-climactic. You achieve the degree, but you actually are stripped of those resources. Leaning on community at that point was really what helped get me out of that funk. Derrick Adams, Derek Fordjour. Those guys, to this day, I'm still really close to them and really use them as resources.

Dani

Absolutely. You talked about having to build this career path, and I feel like in your work—both in its physicality and its concepts—there's a lot of building. I love this idea you have about the artist as the builder of the world. I feel that you're involving a lot of histories and a lot of your own identity in this building. What is the world and the history of that world you're trying to build in your work?

Yashua

I think that "building" in my work is really about construction. Constructed identity, revealing how our identities are really based upon the resources around us. I mean, here I am talking about how my own growth as an artist has really been reliant upon my accessing the resources and the information that I found around me. I haven't mentioned talent, which some people would say talent is something that you're born with, or whatever. That's certainly a part of every artist’s identity—your drive and your ability—but you're built of those around you, you’re built of the resources around you. The physical spaces, of course, the architecture, the literal environment. But then also the beliefs around you. The messages that are around. The ambitions.

"That's certainly a part of every artist’s identity—your drive and your ability—but you're built of those around you, you’re built of the resources around you. The physical spaces, of course, the architecture, the literal environment. But then also the beliefs around you. The messages that are around. The ambitions."

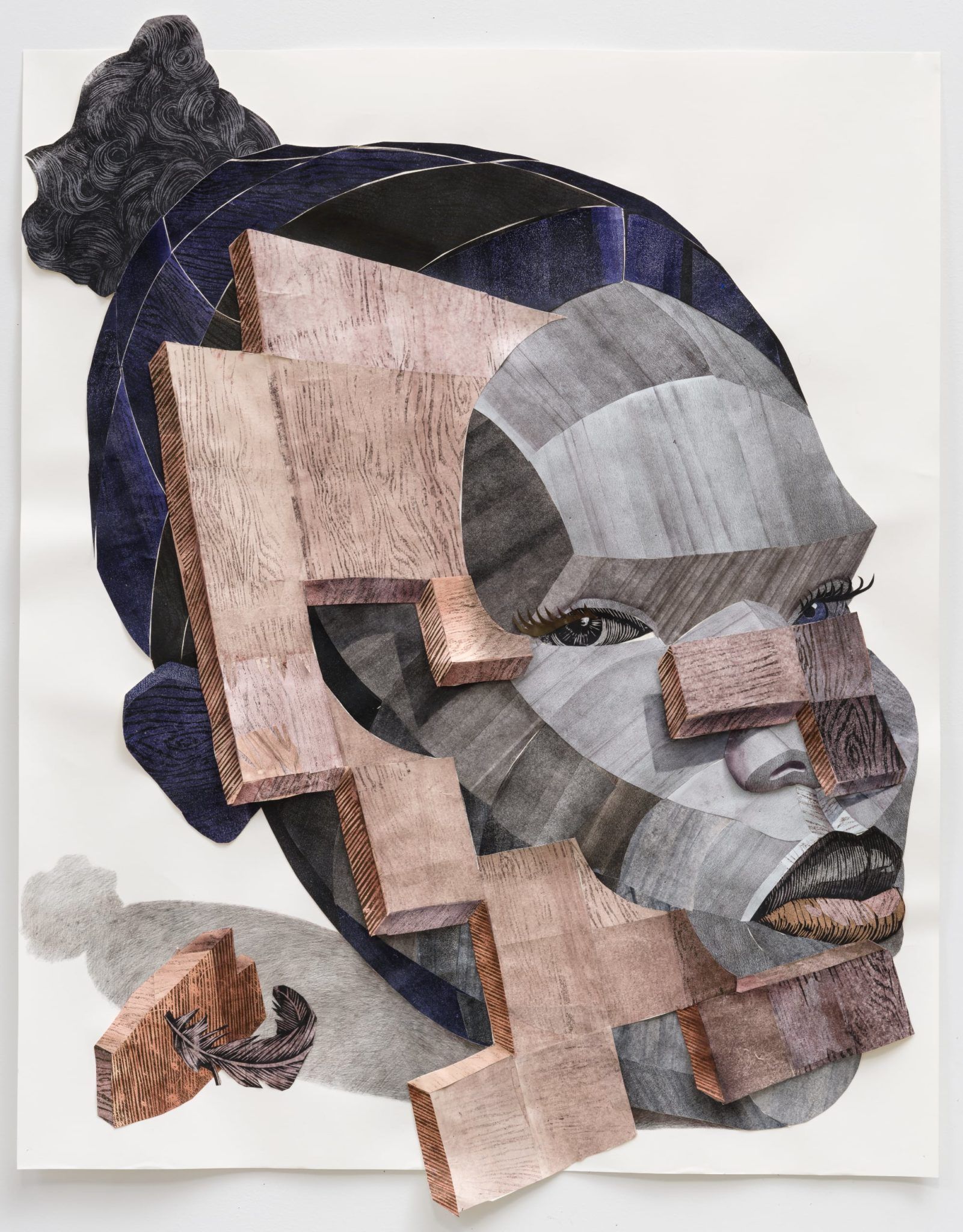

A lot of my work is about that construction of how we believe we are and what we want to project into the world of who we are. And some of that is, of course, idealistic. When you think about civilizations throughout time and the statues they’ve left behind or the monuments they've left behind, from Ancient Egypt and all these other civilizations, there's a proposal of the identity that's very heroic and ideal. We do that also. As humans, we propose a certain monumental identity about ourselves. But I'm also interested in how we're ultimately built of our beliefs, our dreams — all those things are fragile.

When you look at the Sphinx in Egypt, its proposal is that it's eternal. It's literally a lion, so it's royal, it's kingly. But ultimately, it gets weathered over time, it’s changed because of erosion, it's vulnerable to the elements around us, just like we are. That's what I think about a lot in my work. The work is always about these fragments that come together to make the hole. And those fragments reference materials from the built environment around us, whether it's two-by-fours, wood, concrete, or cinder block brick — those sort of elements of the built environment that's around us.

Dani

I love that idea of identity, coming from a combination or culmination of material and spiritual and ideological conditions. You've had a long career as an artist, but you've only recently connected with your father's side of the family. That huge life event must have changed a lot of those conditions for you. As a person and as an artist, what are some of the conditions that have changed for you throughout your career? And how have those changed your understanding of your own identity?

Yashua

Conditions that have changed me. One, moving to New York. I think that definitely changed me a lot. We talked about Chicago as this city that was built for segregation. Being biracial, I was always very hyper aware of the limitations, on where the lines and boundaries were around identities. Around blackness, around whiteness, this and that. Moving to New York, what I experienced was that a lot of those lines were a bit more blurry here, that there was much more integration. And of course we can debate how integrated New York really is, but there's certainly a lot more shared culture here. It's a metropolis. People are arriving every day from other countries and other places in America, bringing culture, bringing new ideas. Here, I feel like there's this sort of constant exchange of ideas. And that really expanded my thinking, just moving to New York.

Another, if I just think about identity-exploding experiences, after I did my BFA, I studied in France for 12 months. And that was a game changer. That was a pivotal moment for me, because I had always resisted the idea of identifying as an American. In America, I never felt like a first class citizen. I always felt not quite American. Obviously, America has a contentious history with Black Americans, and further back being built on land of Native Americans. So I always resisted assigning “American” to my identity. But when I was in France, it was clear to me that, culturally, I was very American. The way I considered time, the way I moved, the way I ate. I would see the French would sit down for two hours to do lunch. And in my mind, I'm like, “We got to get to work. What are we doing? This is wild.” So, that was also really mind expanding — getting out of the country for that amount of time really made me reflect in that way.

Then, of course, like you mentioned, meeting my family was incredibly life changing. So much so that I had to create work in order to find my space within the family, to try to use my artwork as a vessel, as a vehicle to nurture the connectivity with them. That changed my entire practice.

Dani

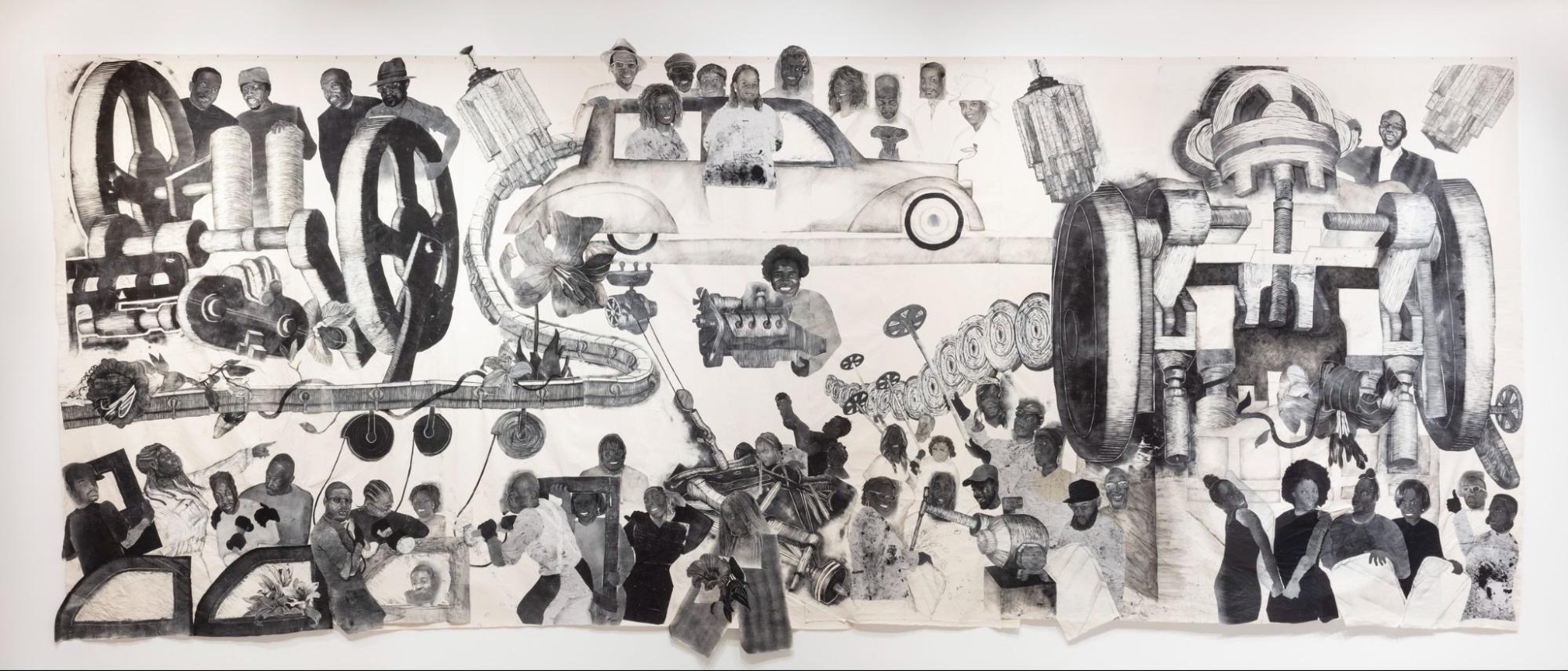

Definitely. That monumental piece, the one that we were talking about earlier, Our Labour, deals with the labor that's involved with reconnection through estrangement, which is something that you went through. The creation of art is labor in its own way. Can you talk a little bit more about what you just touched on? How did the making and exhibiting of those pieces contribute to your reconnection process with your family?

Yashua

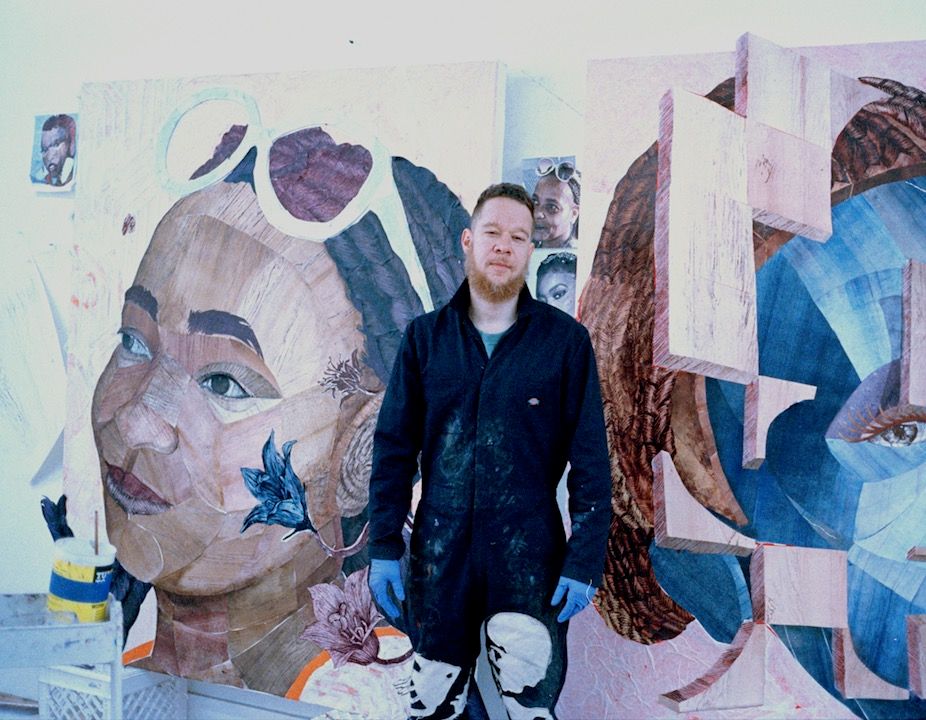

The title of the show, Our Labour, was really important to me, because it touched on a few different kinds of labor. You mentioned one, which is that my work is very process-based. Through durational viewing, you can see a lot of the layers of material and process that go into the work. So, of course, it's about my body and the physical labor that I'm doing to carve blocks of wood, ink them up, create prints. Woodblock printing and collaging is all sort of evident in the work. That's one kind of labor.

The other labor I was thinking about was the work that my family does to stay together. It's a huge family, and they migrated from Memphis to Detroit as very young kids, and found a way to stay together, laugh together, love together, work together, be together. I've just been so impressed by their ability to love and to be generous in that way. And that takes work. It takes sacrifice to do that.

Then also, there's the history of labor for Black Americans, which I'm tracking through my family and their labor in the auto plants in Detroit, and how that labor has been rendered invisible in the telling of American history and the history of cities in the Midwest like Detroit. So part of that whole project was about literally giving faces to that history, making portraits of my family members in order to honor their labor.

Dani

There's a definite monumentality to your work. It feels alive and like it's rooted in the now, but it also feels like you're memorializing and creating a monument to the people and the ideas that are in your work.

Yashua

Thank you.

Dani

Absolutely. I read an interview where you said that you're always looking into the future.

Yashua

I said that?

Dani

Yeah, you said you're always looking very far into the future.

Yashua

I sound like a visionary. Very far.

Dani

You do, indeed. So what are you looking at right now? What does the future look like for you?

Yashua

You know, that's such a good question for me right now. Because recently, I have been so much about staying present. And the reason why is because I did three solo shows last year. It was a ton of work. And when you're working that hard, it's hard to be present. You're always considering the deadlines coming up. You're always thinking about the future, the near future and how close it is. That's stressful. But I just took my first vacation ever, to Morocco.

Dani

I saw that! It looked beautiful out there.

Yashua

Yeah, that was great. And it was so necessary, because it removed me from the stresses of thinking about the near future and remaining present. That's really the headspace that I'm in right now.

Of course, I do have things that I'm thinking about in the near future. I'm doing a show with my Luxembourg gallery. They opened a space in Paris. That's Zidoun-Bossuyt, so I'll do a show there in the fall. And I’m making work for the Chicago Expo, which is in April.

It's funny that you quoted me as saying that I think far into the future, because I think that’s seasonal, you know what I mean? I think sometimes it's healthy to not think too far into the future. Sometimes it's healthy to just be in the present, to be in the now. If I'm being honest, that's where I'm at now. Where I'm at now is grateful. I'm grateful that I have the space to be still and just appreciate and give my all to the moment, to what's right here, and not think too far ahead.

"I think sometimes it's healthy to not think too far into the future. Sometimes it's healthy to just be in the present, to be in the now. If I'm being honest, that's where I'm at now. Where I'm at now is grateful. I'm grateful that I have the space to be still and just appreciate and give my all to the moment, to what's right here, and not think too far ahead."

As humans, we don't usually think too positively about the future. That's what anxiety is, right? Stress is fear of the future. It's very rarely that we have the peace of mind to project positivity into our thoughts about the future. So I'm really working towards a space of projecting my own sense of positivity and comfort around the future. And I know that's very philosophical. I just came from a Muslim country where they have a term, Inshallah: if Allah wills. You can't over-determine yourself about what will become. Of course, you can have your wishes, you can have your desires and dreams, but ultimately, there's destiny and that's what's gonna be. There's a peace, I think, in accepting that. So I'm really in that space right now. Inshallah.